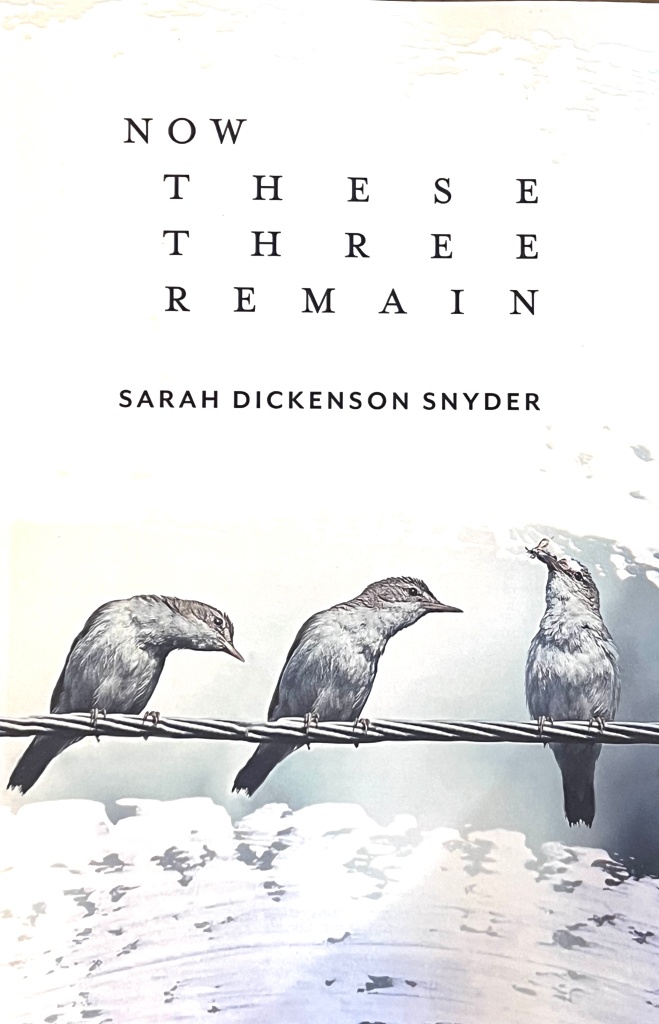

Now These Three Remain by Sarah Dickenson Snyder. Lily Poetry Review Books, 2023. $18.00.

I feel lucky to have acquired several books of poetry from other mature women poets this year: Joanne Durham, Bonnie Proudfoot, Carolyn Martin, Annis Cassells, Nicole Farmer, Alexis Rhone Fancher. All of them different. All of them with distinct voices, interesting stories shared through their poems.

The latest book to arrive is Sarah Dickenson Snyder’s newest work, Now These Three Remain. The very first poem in the book, “When God Listens to Eve”, felt like an immediate connection. The poem begins with the idea that it’s hard to be the beginning, questions our origins, then shows us the rest of the world and, thus, the rest of the book. (If you want to know about the creation of that poem, see Gyroscope Review‘s Origin Stories series from National Poetry Month 2023.) Ms. Snyder offers intimate investigations of being female, questions the choices others would make for us, recognizes love in all its forms, embraces both resistance and acceptance. Politics, religion, war, and climate change ripple through, affecting the personal, shifting the world. Age-old myth lives alongside new pandemic reality. There is assurance that magic might still be found — we can define it ourselves, just as we can define faith, hope, and love.

When I got done reading Now These Three Remain, I appreciated finding another poet who follows, “…what my mind finds / like a planet devoted to spinning…” (from, “To Follow Undisciplined Ink or Having Many Things to Carry”, p. 15). This is someone who sees the world’s savagery alongside its sacredness, then puts that juxtaposition into poems that grab the reader by the throat.

Here are two sample poems, the first from page 30, the second from page 46:

AFTER TWO YEARS OF READING HEATHER COX RICHARDSON I cannot tell if we are on the verge of another ending, the way we lost a collective innocence in the blue blue sky on 9/11. Today humans stir their fear and wrath with guns and rights, icebergs melt and hurricanes and tornadoes whip the fiery wind, floods and virus fill our streets, and truth seems obsolete - is this the beginning of another end? I remember my mother saying, Well, if worse comes to worst, we can always... She had a plan, had something to defrost in the freezer, knew how to avoid cops as she sped along the highway. Now she's hushed in the sediment of our pond - her ashes billowed into a ghost before they settled. Is the world unspooling its heft as it spins and tilts into disaster? I want it to last. I want pesto and breath and maybe a few grandchildren who will swim, held in the cool water, a clear sky rippled on the surface.

WITHOUT REGRET The thrush chirps and flits around my space when I invade the place she's built her nest for four tiny blue eggs, more candy than life. I had to stop watering the hanging flowering plant, watch it wither while something hidden happened inside those eggs. I chose the nest, didn't have to meditate on it very long. I remember finding out I was pregnant when I was too young. I chose my life over what was beginning to grow. I look up into the emptiness and hush of the pewter sky, retrace where I've been over and over again.

The following is the conversation I had with Sarah Dickenson Snyder after I finished reading Now These Three Remain.

OMC: Thank you for this book that feels like such a connection for mature women in particular.

When I read your poems, I kept thinking that we had a lot in common. Being women who came of age when we had choices even as others might prefer we didn’t, being raised Catholic perhaps – which I’m guessing at based on your poem, “Our Holy Symbols Need Attention” – having children, losing parents, being appalled at the state of violence and need in the world, and moving to a new kind of inner understanding of what life can be. I love the way your book begins with Eve saying what she might have wished for as the first woman in the world. What was the poem that first sparked your vision of this book? Or was it more a bunch of poems that seemed to fit together in an organic way, giving rise to the ideas of faith, hope, and love?

SDS: First, thank you, Kathleen, for your time reading and distilling and seeing my work. It’s such an honor when someone does that — a gift from one writer to another. These poems coalesced as a group. I was born into the world as a happy person, and it’s a lens that has never left though it has been shaken and worn down. My writing seems to migrate into places of belief in the mystery of spirituality, the importance of hope even in the worst of times, and most importantly in love and its many forms. I am grateful that my editor and friend, Eileen Cleary who created Lily Poetry Review Books, initially rejected the manuscript. She encouraged me to seek more depth, and in response I struggled and ultimately was awakened in the middle of the night making the connection of the poems to the Corinthians’ verse. [Ed. note: “…faith, hope, and love, but the greatest of these is love. 1 Corinthians 13:1] I rearranged, took pieces out, put others in, and landed at this version of the book.

OMC: That’s so interesting that you say you’re grateful this manuscript was initially rejected. That’s an important point for writers everywhere – the way we get the signal that we’re not quite done with the work, that we must take another look. We have to have enough humility to see those rejections as just that – the nudge that makes the work better. I love that you were grateful.

I noticed a lot of spiritual questioning in your work, alongside a welcoming of awe, so am not surprised to learn that places of belief in the mystery of spirituality is one of the places where your writing migrates. I kept feeling that your thread to the sanctity of the natural world was extended to your readers in these poems. One of the examples that comes to mind is this one, where you contemplate what’s beyond death:

WHERE WE MIGHT GO Rise to a passing cloud, slurry into unencumbered atoms, settle in to deepness of dirt or sea, see a god, sit among rocks, breathe as a body could not, barnacle onto wing, float in acres and acres of air, release need, know before-rain, & bloom what shined inside.

Can you tell me a little more about that aspect of your work – the search, the mystery, the connection with something beyond our human realm, that does not necessarily equate with a belief in a god?

SDS: I’m a bit obsessed with death. I was so frightened of it as a child, just floored that we didn’t get to stay forever. I believe in something spiritual and invisible and mysterious. Organized religion works for many people, gives such strength and power and community. But it doesn’t work for me. I love the stories in all religions. I was a religion major in college because I saw all of them as different paths to the same place, a place of acceptance of death and an uncovering of some kind of divine love. Maybe because I’m closer to endings and because of the deaths of people I love, I can imagine my own in the not as distant future without deep anxiety. The fear has diminished. I’m a hospice volunteer. I’m a Buddhist wannabe. I believe in Martin Buber’s description of the “I-Thou” energy; something divine happens in the “between” when people truly see each other.

OMC: Seeing all religions as a different path to the same place is something I absolutely agree with. We all want to feel safe, happy, loved. And Buddhism, as I understand it, encourages understanding among all rather than dividing ourselves up into this sect and that sect. I’m a fan of Suzuki Roshi’s books. Not so familiar with Martin Buber, so you’ve given me something to look up.

To shift the focus a bit, travel shows up as a great eye-opener in your work. What places have you traveled that stand out as dramatically changing your understanding of how others live on this planet? Talk a little about the places that show up in Now These Three Remain, how they found their way into your poems.

SDS: This is a big question. I love to travel; it makes me be the most present I can be. I don’t know what will happen next; so I have to be alert, aware, and open to amazement. In 2000 when we had sabbaticals from teaching, my husband and I decided to travel around the world for six months and home/world school our kids who were nine and ten. That decision just opened a door that has never closed. Even though I don’t love to fly (that fear of death thing), I am willing to go anywhere. Since then, we’ve taken students to places all over the world. And now, we continue to travel by ourselves or with friends and family. One place that comes up in this collection is Rwanda, a place I’ve been six times. Every time I go, I’m awed by the beauty of the country and the people and can feel a palpable sense of healing from the utter tragedy there. It’s a place I feel completely safe. I also love and hope to return to Thailand, Tibet, Chile, Peru, Vietnam, Cambodia, India, South Africa, Laos, New Zealand, Scotland, Ireland, and Spain. Two of my other collections focus even more on travel: With a Polaroid Camera and a chapbook, Notes from a Nomad.

OMC: Being open to amazement is a fantastic way of putting it. Traveling for six months around the world is something few people get to do. That you’re continuing to travel rather than saying you’ve been there, done that, is right in line with continuing to let yourself be amazed. And that you feel completely safe in Rwanda, of all places, is a nice surprise.

Let’s talk about how people read our work once we put it out into the world, which marks the end of our control over it. What did you hope that people would take from reading Now These Three Remain? Have you been surprised by how this book has been received? If so, in what way?

SDS: These are good questions. I guess I hope that my writing touches someone. Maybe that’s why I let it go into the world, to seek that “between” space that’s invisible and spiritual and real. It’s so crazy that poems reach so deeply into us, that words on a page feel exactly right and uncover what we know is true. I’d love to be able to tell Lucille Clifton that her poem, “blessing the boats,” has softened death for me, that I send it to everyone I love who has someone they love die. I am so honored that you were touched by my work enough to want to learn more about it and me. It’s surprising and affirming.

OMC: Let’s shift the conversation a bit now. How are you feeling about social media right now? As poets, we’re expected to market our own work and that might mean posting as often as possible in as many places as possible. Where do you focus your efforts?

SDS: Though I’m pretty shy and sharing my work does feel like bragging, I do put links to my published poems into the world through Facebook and Instagram. I have in-person and Zoom readings and book launches mainly so the kind small presses that have published my work get business. I want them to stay in business.

OMC: Will you be starting up your blog again anytime soon?

SDS: I’ve been writing the blog when we travel, and we will be traveling at length in February through April; so I’ll probably start it up again then. When I travel, I don’t do much writing of poems, just fill my journal with things that come after the words “I want to remember…” Those images and conversations and observations then work their way into poems when I return. Writing prose for the blog feels more accessible to me on the road.

OMC: Do you have some new projects on the horizon?

SDS: Yes, I have been immersed in a crazy, wonderful project for the past two and a half years. Eve has been speaking with me. The first poem in Now These Three Remain you referenced earlier was the first poem from her. Now there are enough for a manuscript. I’m also learning new things like sculling, embroidering in paper, and knitting—all of that newness gets woven into my writing.

OMC: I can’t wait to see the Eve poems!

Thank you so much for having a conversation with me. It’s a gift to get a glimpse into how another poet finds her territory as a writer and offers that to the world. Are there any last thoughts you’d like to share?

SDS: I feel so lucky to be part of acommunity of writers who share my love of poetry — reading it and writing it. How great to add you, Kathleen, to that inspirational, lovely group. I am humbled by your kind attention to my work and to me. I look forward to reading your work and following your blog. Thank you for all you have done and continue to do to celebrate poets and poetry. If you are ever in Vermont, I’d love to meet you in person, have you up to our home for a meal. I also love to cook!

OMC: I think we would have a great time together. Thanks for the invitation!

For more information about Sarah Dickenson Snyder’s work, please visit her website: https://sarahdickensonsnyder.com/.

If you’re interested in the two previously-published books mentioned in this conversation, here are some links:

Photos provided by Sarah Dickenson Snyder.

One thought on “CONVERSATION WITH POET SARAH DICKENSON SNYDER”

Comments are closed.