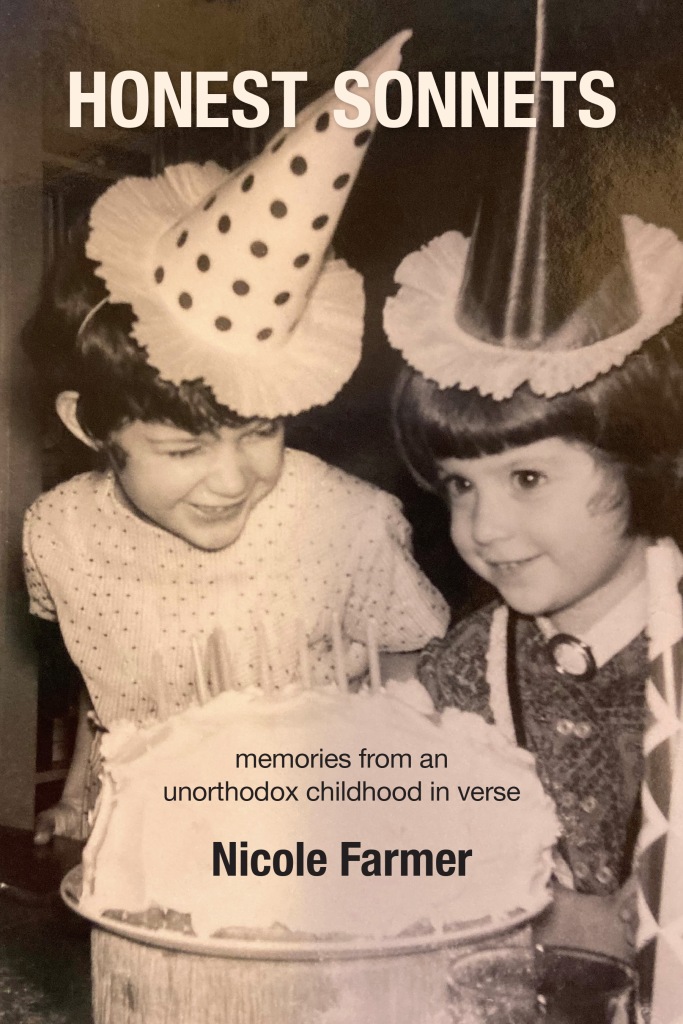

Honest Sonnets: Memories from an Unorthodox Childhood in Verse by Nicole Farmer. Kelsay Books, 2023. $20.00

When I received not one, but two books from poet Nicole Farmer this summer, I was delighted to see that this was another woman poet over 50 hitting her stride. I dove right in to her newest, Honest Sonnets, a memoir composed in sonnets. That is the book I’ll talk about here.

I’m not usually a fan of poetry books that stick to one form, preferring the surprise of poems that meander through whatever form seems to suit them. This book changed my mind. In the author’s note, Ms. Farmer wrote, “I found the restrictions of having to tell a story in fourteen lines, in the structure of a sonnet both comforting and challenging. Something clicked, and for three months the sonnets flowed out of me…” The sonnet form allowed these poems to come together in just the right way, with the structure of each scene, each memory given its own little drawer. It made sense when I thought about the overall narrative: a childhood that lacked a solid structure to call home found its retelling in a poetic structure that offered all the boundaries a child who needed them could want.

Honest Sonnets shows us a girl who lived through tumultuous family dynamics that paralleled a tumultuous time in history. Ms. Farmer was a child of the 60s and 70s whose parents modeled a life of leaping into the moment: free love, drug use, back-to-the-land experiments, going wherever it felt right. The story begins with a child born with a damaged heart. The story then moves from that early trauma, surgery, and healing to the freewheeling existence that would define Ms. Farmer’s childhood. Maybe freewheeling is the wrong word. Maybe I should say freefalling. It felt like the kid in the sonnets was in freefall a lot, hoping for something or someone to catch her.

For me, this was not a book to gulp down in one sitting. I intended to do just that on my first read-through, but stopped halfway to absorb what I’d just read. The poems are intense, each sonnet/story its own little narrative bomb. There are always explosions, some small, some enormous, change the only constant. When I finished reading, I had the sense that this collection is only the beginning. With the life that Ms. Farmer has had, there will always be something to turn into verse, some twist to offer the world.

If I were to choose one poem from this book that is a good example of its scope, I would choose this one from page 27:

LOVE I grew up with this confusing twisting in my stomach. What did the phrase free love mean? I couldn't figure it out. What was happening, when dad disappeared, and mom cried? Where did he go? Why was mom kissing our family friend late one night when I got up for a glass of water? The seventies were a time where what I saw adults do didn't seem free at all, it just seemed weird. Yelling and screaming, throwing dishes and doors slamming, cars peeling out in the night, or hand holding and rolling in the grass on family picnics, laughing and kissing. Up or down, high or low with no middle ground where you knew what might be coming. Except with us. To us they were nurturing. Never wanting us to see the turmoil; we felt it acutely.

It’s the phrase, “…no middle ground where you knew what might be coming,” that gets me. To grow up in such a state of uncertainty is to learn resilience or die. Resilience is exactly what saves us all.

Following is the conversation I had with Ms. Farmer about her work.

OMC: Nicole, thank you for the opportunity to talk about your work and poetry in general. When I read your author’s note in Honest Sonnets, I was immediately drawn to your struggle to define home. This is what so many of us struggle with for various reasons, both from the physical reality of a shelter to the deeper level of what we carry in our hearts. How many definitions of home did you move through as you wrote these poems? Have you found your answer?

NF: Thank you, Kathleen, it’s a pleasure to talk about poetry with you on One Minnesota Crone. This is a question I could talk about all day. Home is a place that many artists talk about in both a spiritual and metaphysical sense as a source for their creativity and a place they have found peace and safety. For many people this evokes memories and deep feeling associated with a particular area geographically and the culture – food, speech, mannerisms, routines- which define them as “southern” or “Appalachian” for example. I grew up with a dad from Chicago, and a mom from upstate New York who carried with them many traditions from their Italian American, and British American roots. Because I moved fifteen times in my first eighteen years, I really felt I had no home, was a constant outsider, except in the company of my immediate family. I grew to rely on them in ways that nomadic tribes experience.

Before I started writing this group of poems, I would have said my family was my home. To some extent that is still true, but because I started writing these sonnets just months after my father and mother died, they came from a place of searching, of true unknowing. I was lost. Only through the writing did I discover that many things make me feel at home, the first being books. Having the security of my favorite books to read, my favorite characters to visit, is as comforting as the familiarity of a church picnic in your hometown might be for some people. The other place I have always felt at home is among trees. A walk in the woods can calm me and inspire like no other place. Of course, whenever I am able to share the company of my husband, my sister, or my daughters, I experience a degree of familiarity like none other, and I know I am home.

OMC: As someone who seldom works in strict forms, I found the choice of sonnets to be an interesting one. You mention in your author’s note that this is the form that just clicked for you, after starting some of these pieces as short stories and prose poems. What nudged you to try the sonnet form at all? Were there other poetic forms that might have worked for this collection? I notice that there are a few poems that aren’t in sonnet form tucked in the book that all ask what and where home is in very short verse, like little road signs. Can you talk about that choice as well?

NF: Good question! I was very surprised that the limits of a 14-line sonnet would be the form that finally clicked! I had taken a few memoir classes and felt really stuck as I had so few photographs to work from, the way Lois Lowry did in Looking Back, for example. I also had a very strict idea of what a Shakespearean sonnet with iambic pentameter, and rhyming couplets, should look and sound like based on my forty years in the theatre and my classical acting training at The Juilliard School. Then I read Diane Seuss’s frank: sonnets, and was amazed how she had blown the lid off the American sonnet and realized I could experiment to my heart’s content.

The short “interludes” in the book came thanks to my good friend and fellow poet, Kathleen Calby. She suggested I break up this dense collection into sections, and as I was deciding where to do this, I happened upon these notes regarding home that I had written in the margins. (I write everything in a notebook first and then type it up later.) They were throw-aways, but I was having fun connecting them to a mathematical equation that reflected the four of us – me, my mom, dad, and sister – and how our numbers changed depending on separations and moves. For example, on page 60, “Where did home go? My sister is traveling. Gone. Now I bounce between two states. 1 + 1 = 3”. In this instance the numbers describe the feeling of being with one parent and how it never seemed to equal 2 in my mind, because the other parent was an invisible presence in the room.

OMC: Your friend had a great suggestion about breaking the work into sections. That works really well. And I liked those little “interludes.” What was the most surprising poem you found yourself writing for this book? Does that same poem still surprise you or do you see why it showed up when you look at the body of work as a whole now?

NF: Gorilla Acres.I really loved living on that farm in West Virginia and have told the story many times, so it surprised me when I reread it and realized that there was so much hidden rage – “fury under my fingernails” – in the narrative. In third grade I was finally old enough to be mad at my dad for an action that he thought was funny but caused me more alienation at school. I think it may be the only poem in the collection that has this kind of open criticism of my hero, my protector.

GORILLA ACRES was what my mom named the place afterwards. She hung a sign just beside the mailbox at the end of the driveway, outside of Union, West Virginia. Our new rental home was surrounded by a thousand acres of grazing land and several hundred cows, a hillbilly paradise until a mob of hunters descended on the old rock quarry with guns, beer and chaw, all because a teenager had seen a "monster" wading in the reeds the morning after he and his cronies went to see "The Creature from the Black Lagoon." We were told to vacate, but dad thought it would be fun to play a joke--sitting on the front porch in a rocking chair, buck naked, he began to jump around and act like a gorilla, scratching his ass, as they came over the rise! Fury under my fingernails, I went to school with the hunter's kids the next day.

OMC: I can imagine how that would infuriate and embarrass a kid! How do you think the pandemic influenced your work on these poems? It was such a time of people reconsidering the homes they were now hunkered down in; did you find yourself reconsidering your definitions of home again at that time and perhaps reworking what you thought you knew?

NF: The pandemic was a very productive time for me. I was working from home as a reading tutor via Zoom. I was grateful to not be traveling to a school and spending my days in the classroom, because it gave me more time to focus on my writing. It seemed to directly coincide with the fact that I had found the sonnet format for the poems and for three months they seemed to flow on to the page at the rate of two or three a day.

OMC: I have a handful of poets that I love to read when I’m trying to find my own right words, like Mark Nepo, Naomi Shihab Nye, James Crews, and Lawrence Ferlinghetti to name just a few. Were there any specific poets you returned to over and over while you worked on Honest Sonnets? Was there anything else that fed your work when you needed some sustenance?

NF: Because my “past life” was spent on stage or directing in the theatre, I spent years reading hundreds of plays and hardly ever took the time to read poetry. When I did indulge, I fell in love with e.e. cummings, Rainer Maria Rilke, and Billy Collins. Now, and while writing Honest Sonnets, I read poetry voraciously, for breakfast lunch and dinner! My current sources of inspiration are Ocean Vuong, Margaret Ray, Sharon Olds, and Natalie Diaz, just to name a few. I also subscribe to dozens of literary magazines like Rattle, Missouri Review, The Pinch, POERTY mag, Ploughshares, Laurel Review, Lit. Mag., The Gettysburg Review, Chicago Review, Prairie Schooner, Iowa Review, Poet Lore, etc., and look for inspiration from new voices.

OMC: The topics you consider in Honest Sonnets could easily evoke strong emotions in other family members, but the best work often comes from a place of emotional risk. How important is taking risks in your poetry? Anything you’d do differently now that this work is out in the world?

NF: My parents died within six months of each other, and I began journaling again and writing poetry daily to manage my grief. Knowing that I could not offend or hurt them by telling the story of my childhood was a freeing realization. Thankfully, my sister has been very supportive. Telling the truth may not be easy, but I don’t feel I would do anything differently. I wrote this collection as a love story to my family. I don’t judge my parents or harbor any animosity toward them for some of their unique life choices. They gave my sister and I endless support and love, and for that I will always feel lucky.

OMC: Your book really is an outstanding story of how we love people no matter what their flaws and talents are as long as we feel loved and supported in return. This is what binds us to one another. What’s next for you?

NF: I have begun working on a new group of poems under the working title Open Heart. It started when a local reviewer asked me if I had any poems specific to western North Carolina, and I admitted I did not. My poems are usually centered around people and relationships. I have been writing about the discovery that having open heart surgery at the age of three truly shaped me. The way I rush at life, with trust and assuming the best, as if each day or breath might be my last. The way I have always loved fiercely and deeply, as if my existence depended on it.

OMC: I look forward to seeing that work in the future. Thank you so much for taking the time to discuss your work and share your insights.

BONUS POEM

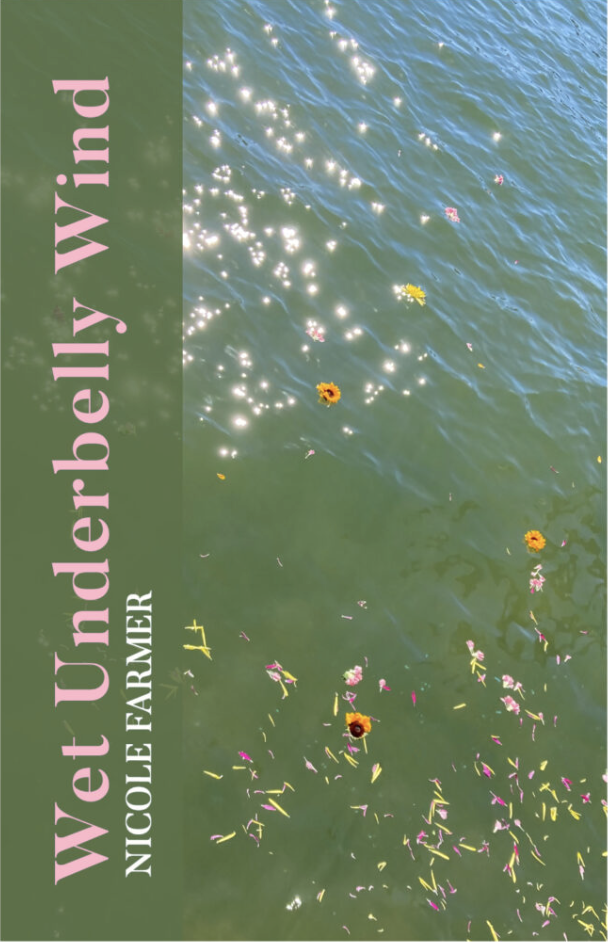

The second book Ms. Farmer sent me was her chapbook, Wet Underbelly Wind (Finishing Line Press, 2022. $15.99). I read it after I started writing the interview questions for Honest Sonnets. As I was reading, this poem from page 9 seemed just right to share here at One Minnesota Crone.

SHIBUI LIST Saying no. Not caring when you laugh too long or clap too loud. Realizing you're just as fabulous in Keds as stilettos. Appreciating your friends and their ability to make you smile. Knowing you look better without make-up, but never giving up lipstick! Being just as happy with a quiet day in the garden and reading a good book, as you would with dinner and a show. Taking nothing for granted. Welcoming the idea of no longer being valued for your sex appeal alone. Feeling weaker of body and stronger of mind. Having a good chuckle over failure, instead of a crying jag. Smiling when others cut you off in traffic. Looking forward to your morning cup of tea. Noticing tree blossoms. Smelling the rain. Enjoying the success of your children more than you enjoy your own. The beauty of aging.

Find out more about Nicole Farmer’s work at her website, NicoleFarmerpoetry.com.

Photos provided by Nicole Farmer.