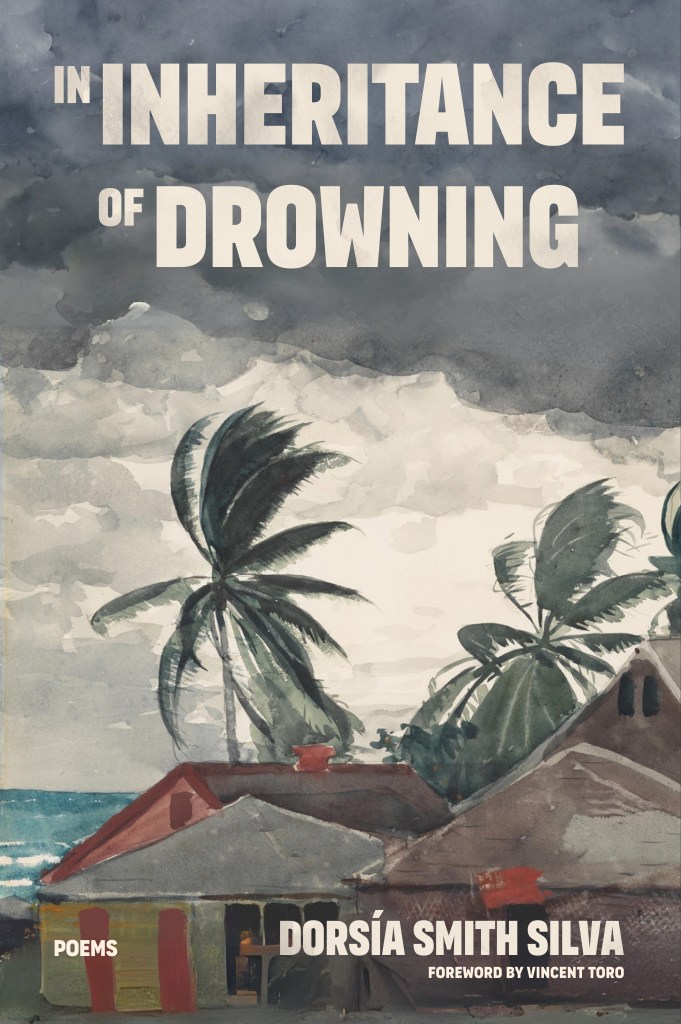

Welcome to another installment in One Minnesota Crone’s Conversation with a Poet series. Today’s poet is Dorsía Smith Silva, poetry editor at The Hopper, editor of Latina/Chicana Mothering, co-editor of several other books, and professor of English at the University of Puerto Rico – Río Piedras. Her soon-to-be-released poetry collection, In Inheritance of Drowning, (CavanKerry Press), is the topic of today’s conversation.

I had scant knowledge of Puerto Rico before I read In Inheritance of Drowning. I knew it was devastated by Hurricane Maria, that the US didn’t do enough for all the people affected. As part of my research while reading In Inheritance of Drowning, I read a Time Magazine piece published shortly after the Hurricane Maria’s havoc which stated nearly half of Americans don’t know Puerto Ricans are American citizens. Crushing debt and fragile infrastructure made – and continue to make – Puerto Rico’s recovery exceedingly difficult. Even though it’s been seven years since Hurricane Maria roared across Puerto Rico, people still suffer. Subsequent difficulties due to the pandemic and earthquakes hammered away further at Puerto Rico’s residents.

But In Inheritance of Drowning is about more than Puerto Rico. It’s about the assorted ways that people, especially people of color, drown. Yes, there is water that rushes over communities during a hurricane. But people also drown from debt, oppression, racism, misunderstanding. People sometimes drown because of actions by others, actions based in greed or ignorance or, alternatively, from inaction caused by simply not caring. As Vincent Toro says in the book’s foreword, “it is essential that the island’s writers provide us with testimonios that allow us a clearer path to understand what it means to live through and beyond disaster.”

In Inheritance of Drowning is, at its heart, a collection of protest and political poetry. It is a call to action, an insistence to find a more compassionate way of living in this world, a life preserver tossed to any outstretched hand.

It is also a celebration of the resilience necessary to go forward.

I’m honored to offer this conversation with Dorsía Smith Silva about her work.

OMC: Dorsía, thank you so much for having a conversation with me about your work, and congratulations on the upcoming November release of In Inheritance of Drowning. When we first corresponded about this conversation, it was around the time that Hurricane Ernesto hit the Caribbean, causing yet another power outage and delaying the start of public school in Puerto Rico. It’s interesting that In Inheritance of Drowning is coming out during hurricane season in an election year. Was that planned or was that coincidence? Are you pleased with the timing?

DSS: Thank you so much for having this conversation with me, Kathleen. I am very happy and grateful to be here!

My publisher, CavanKerry, decided to release In Inheritance of Drowning in November. I think that was primarily due to the scheduling calendar, but I think the timing has been auspicious. The hurricane poems in In Inheritance of Drowning are all the more meaningful, especially with the anniversary of Hurricane María on September 20th. The political poems in the book also connect to the elections, since they explore the meaning of social transformation. The book will be released after the elections though, since my publisher and I realized that most of the national attention (and rightfully so!) will be on the United States presidential election and several significant propositions. I am looking forward to the book’s release on November 12th, and celebrating the book being out into the world.

OMC: In an interview that you did with Cream City Review, you said that you kept a journal about your experience during Hurricane Maria and its aftermath, and this is what spawned the poems that became In Inheritance of Drowning. There’s a rawness that is captured when writing during an experience, but there’s a refinement that only happens later when a writer gets some distance from the original idea. At what point did you feel like you had sat long enough with those journal entries that you could put them into poems? Or were you making poems all along the way while writing in your journal, poems that you later edited? Did this work help keep you grounded during the initial disaster recovery efforts?

DSS: I was writing poems along the way while writing in my notebook. However, I did not realize that they were poems until much time had passed after Hurricane María. I did not look at my notebook for a long time because I was in survival mode, and I think there was some fear of what I had written. Would it be too painful to revisit those memories? Would it bring another layer of trauma to open the notebook? It took months before I was comfortable to open the notebook, and when I did, I was surprised that I had written all kinds of poems—prose, narrative, and lyric. Other poems were strings of thoughts, random words, and phrases. Keeping the notebook and returning to the notebook helped me feel calm. There was so much uncertainty during the recovery efforts that writing felt like a safe and reliable process. Writing to me is still a process that I trust; it makes me happy.

OMC: You framed the book with the hurricane poems, but the middle section leaves Puerto Rico to examine other ways people, particularly people of color, drown in the United States. As I read these poems, especially Everyday Drowning, I found myself counting the names of people killed by the police in the Minneapolis area where I live – Philando Castile, George Floyd, Amir Locke, Duante Wright. I’d like to quote part of stanza 4 from that poem here:

gone quickly

gone slowly

without prayer

in prayer

gone from history

in plain sight

in quiet

without questions

with questions

at any cardinal direction

waiting

on a cold day

on a warm day

outside the law

inside the law

without air

with air

without blood

in blood

on the news

at anytime

on any day

in our homes

in any city

What struck me is the way you bring in the anywhere-ness of oppression so well here. Any city. My city. Your city. This brings the collection to the front doors of all your readers. What went into the decision to frame the book this way, to shift the focus from Puerto Rico’s boundaries to the broader scope of struggles in the US? I know you’ve addressed this in other interviews and think it’s worth reiterating here.

DSS: The oppression of Puerto Rico is linked to the oppression of BIPOC communities in the United States, especially since it is the same systemic dismantling of identities, violence against Black and brown bodies, and political, social, and racial injustices. I also wanted to show how Puerto Rico has been harmed by the colonialism of the United States in the same ways that BIPOC communities have been affected in the United States. The end results are socioeconomic inequalities, political and financial strangleholds, and the “drownings” of Black and brown bodies. I think In Inheritance of Drowning had to reflect upon Puerto Rico and the United States to show this complex relationship. Sometimes, people are unaware that Puerto Rico is actually a colony (not a territory) of the United States, and this subordinate status begs the question, “When will Puerto Rico be free?” It’s the same question that BIPOC communities may also ask: “When can we be free from oppression in the United States?”

OMC: Thank you. I wish we could say those questions are going to be answered and acted upon right now. There’s work to be done by all of us.

Your book pushes readers to consider what they see in this world, where help might be offered, where beauty can still be appreciated, where rebuilding must happen for a better future for all. What do you consider the most hopeful poem in In Inheritance of Drowning and why?

DSS: Thank you for acknowledging this in the book! I hope other readers glean this important message as well—about beauty and rebuilding. I think the opening poem reveals a sense of hope. Hurricanes do not have to be “skylights of horror,” if we humans made more of an effort to combat global warming. If we saw our connection to the environment—let’s say as kin—, then we would hopefully make better environmental choices, which in turn would decrease the number and strength of hurricanes. The effect would be less destruction, loss of lives, and financial ruin. Hurricanes would then just be beautiful bright colors on a weather map. We could see them as having “intoxicating possibilities and mysteries” without their trauma and widespread damage.

What the Poet is Supposed to Write about a Hurricane

What the poet is supposed to write about a hurricane

should be skylights of horror,

not skip rocks of beauty in walls of wind,

affixed to the puzzle pieces of the vortex eye,

spinning like a lost continent’s soul.

How the lively whips should stun the mouths of gravity,

hissing without hesitation,

engulfing the stench of uprooted dirt and grass.

The poet is supposed to decode the stanzas,

shudder the name María

into frail syllables:

to wish a hurricane a fast and gritty death,

not say its stubborn slow dances

held intoxicating possibilities and mysteries.

OMC: Oh, that’s a perfect poem choice. And your idea of treating other living creatures as kin instead of something separate – that’s something that resonates for me. Our environment is our home. We must take care of it.

Do you plan on continuing to explore the issues examined in In Inheritance of Drowning in future works? Anything on the horizon?

DSS: This is an excellent question! I am currently working on poems that examine the many Puerto Ricans that were forced to flee Puerto Rico after Hurricane María. Some of these poems will be about the precarious political and environmental conditions in Puerto Rico that were exacerbated after Hurricane María, and other poems will be about the social, political, and racial inequalities in the United States. I am also composing some poems that explore the psychological turmoil that occurs when people are displaced from their homelands. I am excited to see where this collection will take me.

To celebrate In Inheritance of Drowning’s birthday, I am going to challenge myself to read a poetry book by a BIPOC author every day in November. I am going to model the challenge after the Sealey Challenge and call it the Smith Silva Challenge. I am looking forward to reading for fun and just diving into a pile of books! There are several poetry books that I cannot wait to begin, including Danez Smith’s Bluff and Eduardo Martínez-Leyva’s Cowboy Park.

OMC: I’ve done the Sealey Challenge; I love that you’re creating the Smith Silva Challenge for BIPOC-authored poetry books! What a great way to celebrate. And I very much look forward to seeing more of your poetry in the future.

Thank you for sharing your process and insights today. I hope you have a wonderful release party planned! Anyone you’d like to give a shout-out to before we wrap up?

DSS: Thank you so much again, Kathleen! I would like to thank Shara McCallum, Frances Richey, Derrick Austin, and Velma Pollard for writing such wonderful reviews of In Inheritance of Drowning. A million thanks to Vincent Toro, the author of Hivestruck, for writing the introduction to In Inheritance of Drowning. The introduction is brilliant; I was ready to cry after I had read it. I also want to thank Poets & Writers for including me in the Get the Word Out and 5 over 50 cohorts. Their support has been life-changing.

It was such a pleasure to have this conversation. Many thanks, Kathleen!

In Inheritance of Drowning is available from CavanKerry Press HERE.

Find links to Dorsía Smith Silva’s interviews and publications through her website HERE.

Follow Dorsía Smith Silva on Instagram @dsmithsilva.

I learned a lot from this interview. Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person